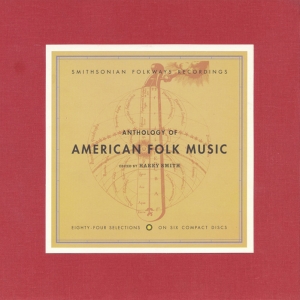

Anthology of American Folk Music

Harry Smith

NY Times -- August 24, 1997

POP VIEW / By TOM PIAZZA

Occasionally a single artifact, document or exhibition manages both to

recast the way in which artists see their tradition and to reanimate their

sense of what is possible within that tradition. Such cultural moments act

as prisms, gathering together work from different ends of a genre's

spectrum and allowing them to blend in a new way.

One such document was Edmund Wilson's 1943 anthology "The Shock of

Recognition," which assembled two centuries of American writers talking

about one another's work.

In the process, it illuminated the grand sweep and vigor of American

literature.

Last week, Smithsonian Folkways records re-released another such document,

the "Anthology of American Folk Music," originally issued by Folkways

Records in 1952. The brainchild of the avant-garde filmmaker, folklorist

and anthropologist Harry Smith, the anthology comprised three boxed two-LP

sets that contained 84 performances recorded between 1926 and 1933.

Included were early black blues and white country music, Cajun recordings,

hymns and sacred music, and more, thrown together under a loose framework

that almost single-handedly redefined folk music.

In doing so, the anthology became the single most important source of

material and inspiration for many young singers in the 1950's and 60's and

the touchstone of the early-60's "folk revival." Such performers as Bob

Dylan, Joan Baez, Phil Ochs and the New Lost City Ramblers, as well as

later offshoots like the Byrds, Bruce Springsteen and Jerry Garcia, owe not

just repertory and techniques but, in a real sense, a large portion of

their world view to the anthology's conflation of such seemingly different

traditions.

The package appeared on the small but important Folkways label, run by

Moses Asch, who had recorded performers like Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly and

Pete Seeger, and thought of his label as a great aural museum. Before

issuing Harry Smith's Anthology, Folkways had released a series of

compilations of various ethnic musics as well as early jazz music. But

Smith's project was different.

The anthology itself seemed to have a personality, much like that of its

compiler: erudite, hermetic, witty in a deadpan way. The cover of each

boxed volume was plain black cardboard, with the selections and performers

listed plainly on a label affixed to the front. Volume 1 contained ballads

(songs with a narrative content), Volume 2 was titled Social Music (dance

music and religious music) and Volume 3 was a catchall called Songs,

offering vocal selections with no real narrative aspect.

(The six-disk reissue wisely follows the exact format and sequence of the

original.)

Each box contained a copy of a booklet written, designed and laid out by

Smith himself, an idiosyncratic compendium of discographical information,

bibliographical references and summaries of the songs, all set in various

type fonts and illustrated with photographs, advertisements from old record

catalogues and other ephemera.

The music itself on the anthology opens a door to a world that will be just

as strange to most listeners of today as it was in 1952, and perhaps more

so. The lyrics offer a panorama of murders, religious visions, hangings,

agrarian complaints, heroic exploits, swindles, assassinations and endless

traveling. The extraordinary range of vocal sounds in which these marvels

are expressed is no less wondrous. The nasal timbre of the coal miner and

banjoist Dock Boggs on his two 1927 recordings included here, or the

rasping throat tones of the religious street singer Blind Willie Johnson,

so different from each other, both still carry the power to shock 70 years

after they were recorded.

The vitality and variety of the music are staggering, from the country

singer Uncle Dave Macon's hollering, headlong vocal and banjo on "Down the

Old Plank Road" to the inwardness of the New Orleans songster Rabbit Brown

on his "James Alley Blues" to the pinched, wry, tall-tale quality of Kelly

Harrell's small 1927 masterpiece "My Name Is John Johanna," a song about a

laborer's disastrous trip to Arkansas in search of work. Several pieces,

like Buell Kazee's "East Virginia," have the odd-sounding modal harmonic

quality of English ballads; elsewhere one finds Anglo-Irish fiddle tunes,

Cajun dance music from Louisiana and collective ensemble gospel singing by

black and white groups that rivet you to your spot by their intensity and

commitment. Many of the performers remain obscure even to this day. ÊÊ ÊÊ

he performances were originally recorded commercially by

companies that were trying to compete with radio in the 1920's by finding

new markets among the people of the rural South. The 78 rpm records were

often designated as "hillbilly" or "old time" (euphemisms for rural white)

and "race" (euphemism for black). What Harry Smith did that was new was to

throw these recordings together, with no regard for the commercial

categories for which they had initially been recorded.

The booklet resolutely avoided mentioning the race or ethnicity of

performers, and many of the songs that were included cropped up in both

black and white traditions. The rationale for listening to a performance on

the anthology's terms was not that it represented the voice of a specific

ethnic group; rather, strangeness, passion and mystery, the anthology

seemed to proclaim, are universal human traits.

It was a revolutionary message and is still so today, when so many claims

of identity are staked along ethnic lines.

Smith's cultural Trojan horse rolled into public view at the beginning of

the Eisenhower 1950's, in the wake of World War II, as America was asking

itself in many ways, not all of them healthy, what it meant to be American.

Powerful currents of standardization were all around; anxiety about fitting

in, assimilating, returning to normalcy after the war and a residual sense

of threat from outside quickened the impulse to locate a common denominator

in behaviors and values. It was the period in which Levittown was born.

Into these currents strode the anthology, implicitly asserting the

multifarious, the odd, the local as being somehow definitively American.

That apparent paradox appealed to those who wanted to see behind the

conformist scrim of the Eisenhower era. To them, the anthology was a sort

of palimpsest wherein they read a secret cultural history of the nation.

Among these were the young men and women who made up the folk revival. Many

of them, like the members of the New Lost City Ramblers, a traditionalist

group, strove to recreate the original performances in as faithful a manner

as possible; others used the anthology as a trove of material to mine, and

transmute. Bob Dylan is certainly the best example of this; his earliest

performances were full of material taken from the anthology. Echoes of

lyrics from anthology songs continued to appear in Mr. Dylan's later works.

On his most recent disk, "World Gone Wrong" (1993), he performs several

tunes that appear on the anthology.

If the anthology energized a new generation of performers it did the same

for a new generation of folklorists, mostly white and mostly male -- among

them Mike Seeger, Ralph Rinzler and Paul Clayton -- who traveled south in

hopes of finding the original performers. An amazing number of them turned

out to still be alive; the Newport Folk Festivals of the early 1960's

offered a procession of them -- Clarence Ashley, Dock Boggs, Mississippi

John Hurt, Furry Lewis, Buell Kazee and others -- in one of the great

reclamation projects in American cultural history.

The re-issue of the anthology is the most significant event yet in

Smithsonian Folkways' superb reactivation of the original Folkways

catalogue, which the Smithsonian Institution acquired in 1987, after Mr.

Asch's death. Smithsonian Folkways has taken care to allude repeatedly to

the original anthology in its repackaging.

Included is a reproduction of the original booklet as well as invaluable

supplemental notes, an expanded bibliography and references to other

recordings of the same material by other artists.

There are essays on the anthology's effect at the time, including a

wonderfully pointed one by the folklorist Jon Pankake, as well as

reminiscences of Harry Smith, who died in 1991, by those who knew him.

The re-issue also features a long essay by the writer Greil Marcus

excerpted from his recent book "Invisible Republic," which offers insights

into the anthology's place in American culture. Not included in the

package, but worth reading, is a chapter in Robert Cantwell's recent book

on the folk revival entitled "When We Were Good," which puts Smith's

achievement in lucid historical and cultural context. The current set's

sixth disk is an enhanced CD offering photographs, biographical material

about Smith, video footage and linkage to an Anthology Web site.

Somehow, in the process of gathering all its voices together, the anthology

became not just a loose confederation but an integral unit, a whole made up

of the most disparate parts, like some ideal America of its own. It was a

gauntlet thrown down, in a sense, a challenge to ponder: what kind of unity

could possibly underlie this diversity? It is a question we still ask, and

the re-issue of this milestone set helps us ask it in appreciative wonder.

All Materials ©2025 David Larstein Music

All Materials ©2025 David Larstein Music

Web Design & Development by Sleepless Media

Web Design & Development by Sleepless Media